Exhibition: Future Fossil Spaces, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

The exhibition brings together works for which the artist travelled to Iceland, Kazakhstan, the Atacama Desert (Chile), Bolivia and Argentina. It is entitled Future Fossil Spaces, a title which is a nod to The Blue Fossil Entropic Stories, three photographs which were taken during an expedition undertaken in 2013, when Charrière climbed an iceberg in the Arctic Ocean and attempted to melt the ice underfoot using a gas blowtorch for over eight hours. The fossils mentioned in this instance do not refer to animal or mineral traces captured in rocks but to the Latin etymology, which literally means “obtained by digging”, where the artist’s action involves presenting, there and then in the exhibition space, works which are in dialectic conflict between the two arrows of time, one pointing towards the past and the other pointing towards the future.

One of the works, the most understated in the exhibition, is entitled The Key to the Present Lies in the Future (2014). Twenty-four hourglasses containing sand from twenty-four geological periods are hurled by the artist against a wall of the Museum. All that is left of all those eras suddenly brought together in the same place and at the same time as a result of a powerful act are glass debris and sandy remnants. The hourglass itself is already a perfect metonymy of the link between time and space since it allows an interval of time to be measured by the movement of matter. The work echoes that of Robert Smithson, and in particular his thoughts on the issue of non-sites, and recalls one of his works in particular, Hypothetical Continent (Map of Broken Glass: Atlantis), created in 1969, a pile of glass fragments which make up the fictitious map of a lost continent.

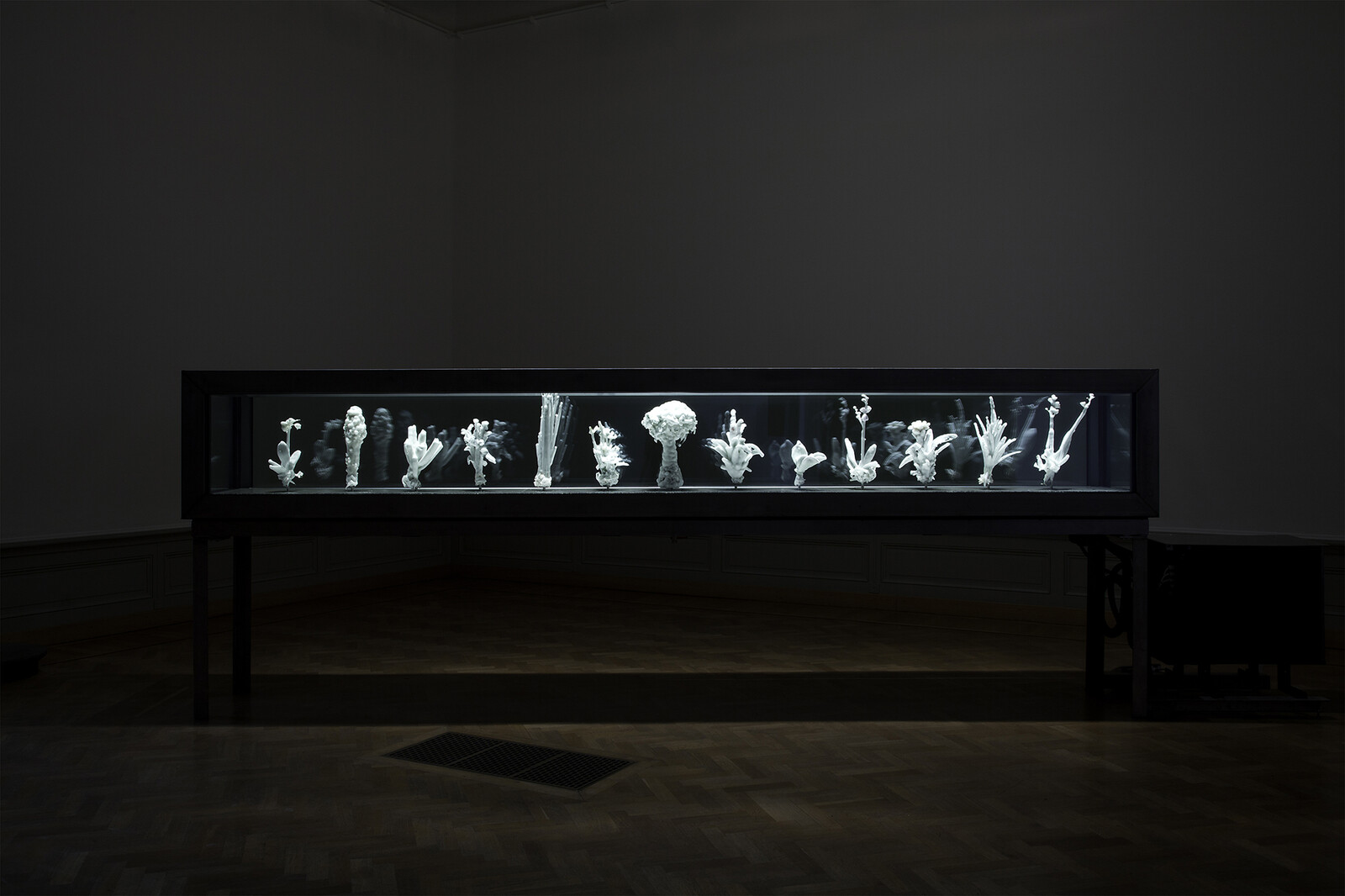

Rather than a hypothetical continent, Julian Charrière lays out a fictitious topography, a sort of “energetic garden”, in the exhibition. On the ground, there are strangely beautiful coloured landscapes made from enamel- led steel containers full of saline solutions from lithium deposits in Chile, which resemble an aerial view of the deposits; rising high, columns of salt bricks from the same area highlight the tension between a material of the future – lithium – and the time which has had to elapse in order to create it; further on time seems to be frozen in a display cabinet where the artist has deposited plants captured in a sheath of ice; finally, a video filmed in Kazakhstan, at the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, closes – or opens – the exhibition on the issue of the interdependence between humans and their environment. Entitled Somewhere, the video explores the site of the first Soviet military nuclear tests, where the radiation which was re- leased between 1949 and 1989 remains extremely high today. The desolate and timeless aspect of these landscapes, filmed in a slow motion tracking shot by the artist without any accompanying commentary, lends an unsettling strangeness to them. The past catches up with the future in a constantly expanding present.